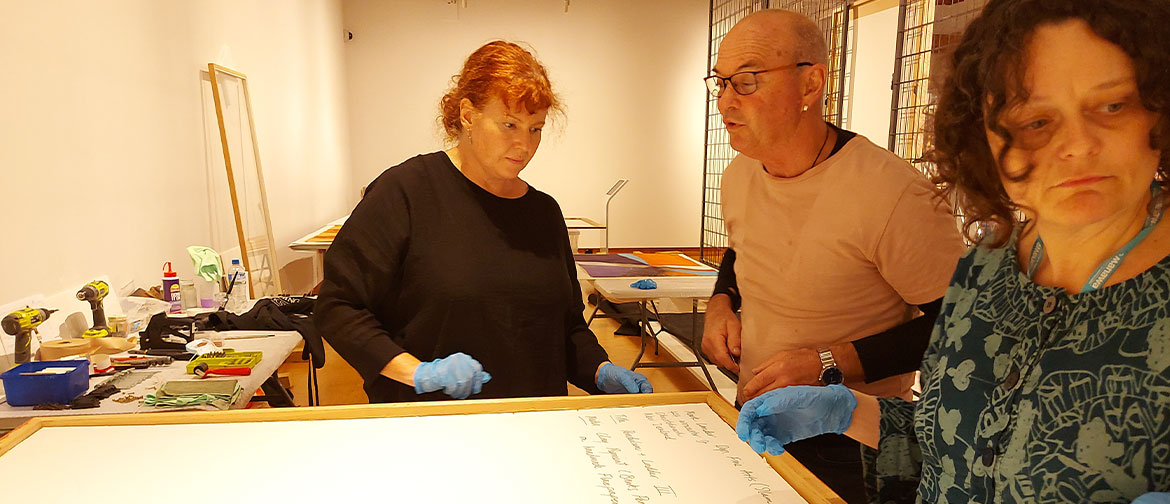

Photographer Jess O’Brien, framer Keith Stewart and collection manager Talei Langley prepare a large framed artwork for photography.

The corner of the collection store is elaborately illuminated, a bright oasis between the darkened racks of objects. At the heart of the lighting, Te Manawa staff gently manoeuvre a heavy Māori piupiu onto a table. A photographer stands poised to climb a tall ladder; first she will capture the skirt from above, and then from a dozen other angles, making sure no detail is missed.

It’s a demanding process. To document the 40 or so piupiu that the museum cares for has taken two whole days. As the effort winds down, everyone’s looking forward to a cup of tea and not, for now, thinking about all those other objects around them that they’ll have to get to sooner or later.

They’ve crossed another 40 objects off the list. Only about 40,000 to go.

Documenting these taonga is part of Te Manawa’s long-term plan to move its collection into a new era of visibility and ease of access. Thousands of objects and artworks can now be viewed online, a colossal endeavour that staff are approaching the only way they can: one day at a time.

“It’s a mammoth task. It’s years of work,” says Collection Manager Talei Langley simply. “The photography started well before I got here last December, and I’ve been working on it ever since.”

“You’ve got to consider staff availability, how many people can you get doing it. It’s time with scanners, time with photographers. It’s time.”

A daunting prospect, to be sure, but during the past few years Te Manawa staff have given themselves a head start, photographing their way through the art collection. That’s all the framed paintings that’ve been rotated through the rack display in the Art Gallery, all the works on paper, the ceramics and the sculptures.

“The framed works with glazing were a big effort,” recalls Talei. “It’s very difficult to photograph shiny things. Our photographer had an elaborate set-up using polarised lights, so if she did it just right they would cancel out the glare. It was amazing! She could photograph through glass in a way that’s almost impossible.”

The art collection is close to three thousand items, more than enough to keep the most avid art lover going for weeks. The heritage collection, however, is upwards of fifteen times that, stored in areas far more extensive than the part of the museum seen by visitors every day.

How does a museum go about photographing something so vast? Where to start? Collection Manager Cindy Lilburn had to come up with a simple method to avoid being overwhelmed.

“She’s doing chunks of things she thinks the public will find interesting,” says Talei. “For the initial launch we have militaria, pasifika and a collection of childhood items.

“There’ll be stuff there that’s never been displayed,” she continues, her eyes lighting up. “From a gallery perspective and a curatorial perspective, that’s really exciting.”

The rāranga collection – including the 40 piupiu – will join them soon. As taonga Māori, they cannot be shown publicly until the museum has been granted the necessary cultural permissions.

Talei takes a deep breath. “And then there’s the whole copyright side of it!”

Even though an artwork is in our collection, the artist still holds the copyright, and the museum cannot reproduce it without their permission. A work leaves copyright 50 years after an artist’s death, so if an artist died before 1972, Talei need do nothing further. However, if there’s one thing Te Manawa’s art collection is known for, it’s a rich variety of art from the mid 1970s and onward!

“I’ve been prioritising working with artists who have lots of art in the collection. The top 50 artists represented there make up more than a third of it,” says Talei. “If the artist is dead but 50 years have not yet passed, we have to track down the copyright holders. It’s usually family, but sometimes there have been trusts set up, or they could have appointed someone else. It means lots of research, lots of calling colleagues at other museums to ask ‘hey, do you know who holds the copyright for this artist?’”

The collection is viewable online via the Te Manawa website. The search tools are quite powerful, using a kind of AI that allows visitors to browse not just by artist or title, but by meta categories like size, shape or even colour.

“If you type in ‘fan’ it won’t just give you items that have that text, you’ll get things the AI thinks could be fans. It’s got a bit of cleverness behind it,” explains Talei. “We really wanted to include these fun ways into the collection, so you didn’t have to search for specific artists; you could just say ‘show me all your green things!’ and have a look.”

Talei hopes that this resource will be a huge asset, not just to the public, but to the wider museum sector too – and that includes Te Manawa itself.

“Knowing what’s out there is half the battle. If curators don’t know what we’ve got they’re never going to end up in shows! I’d like to see a lot more loans to other institutions, and the collections getting out there more.”

Website visitors will have access to out-of-copyright art that they can use for any purpose, and Te Manawa can put them in touch with living artists whose work interests them. They can assemble their own mini collections using the online tools, which will only get more diverse as more objects and artworks go up.

“People understand the value of things being online, especially since Covid,” says Talei. “We’ve got the basics in place; now we can work on areas of the collection that are more fun and experimental.”