Bagatelle game, c. 1940s, estate of Archibald Iverson Tiller, Te Manawa Museums Trust, 93/142/476.

You have probably played a ‘pinball machine’ at some point in your life and are as familiar as I am with the standard variety of table-top game produced commercially during the late 20th century through to the present. I remember one I was given in the 1950s made of printed tin with a plastic cover to prevent the balls from being lost. The mechanism to launch the balls onto the ‘playing field’ was spring-loaded with a wooden handle that was pulled back to fire the ball.

Pinball machines have a number of predecessors, the most significant being ‘bagatelle’.[i] Te Manawa’s bagatelle board is, we believe, a home-made copy of the commercially-produced game of ‘Taipo’. Upon examination, it is possible to see that the game board is made from wooden packing case slats (probably pine) with pieces of building timber (possibly tōtara) for its sides. On the underside a piece of wood bears a portion of a painted design such as applied to packing or shipping crates. The rounded end is formed with a semi-circular strip of galvanized iron. On the right side there is a track along which the balls would have been fired. The game includes 19 rusted steel ball bearings, but the launching mechanism is missing. The bagatelle board is portable, measuring 60 cm long, 27 cm wide and 7 cm high, and is intended to be used on a table.

The board slopes slightly upward to allow the balls shooting out of the track to cascade down the body of the game. Nails have been used to create a pinball course to direct the balls to the numbered holes or to interfere with their movement and allow them to return to the bottom portion of the game where they can be reused by the players. Nails in a V-shaped configuration trap the balls, as do a few ‘unprotected’ holes. The player who had the most balls trapped on the board was awarded ‘points’; the most points determined the winner if playing competitively, maybe with a friend or family member. Potential scores are pencilled by most holes and also where balls may be lodged. The holes in the side rails were used to keep score using a nail or pin as counters; the nails or pins were advanced along the rail as scoring increased. Several initials can be seen pencilled on the side rails to identify the players.

Bagatelle game, c. 1940s, estate of Archibald Iverson Tiller, Te Manawa Museums Trust, 93/142/476.

History of the Bagatelle Game

The name ‘bagatelle’ is said to be derived from the Italian bagatella signifying ‘a trifle’ or ‘decorative thing’. It is also associated with Château de Bagatelle in Paris, owned by the Count of Artois, younger brother of Louis XVI. Apparently, at a party held at the château in 1777, a new table game was introduced in which players shot small ivory balls up an inclined playing field using cue sticks (similar to pool cues). The game was dubbed ‘bagatelle’ by the Count and became widely played throughout France.[ii] It is believed that during the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), French soldiers fighting against the British on the American side carried small bagatelle boards with them. Interest in the game spread and it became popular in America and elsewhere.[iii] ‘Spanish mahogany Bagatelle Boards’ were first sold in New Zealand by John Montifiore, a Jewish trader from England, in 1840.[iv] A bagatelle variant using fixed metal pins and a glass panel over the playing field eventually led to the creation of pinball and pachinko (a vertical pinball machine). The popularity of bagatelle continued well into the mid-20th century.

Playing games of chance is a distinctly human practice. Games such as marbles, bowls, skittles, tic-tac-toe, and mumbly peg (or ‘stick knife’), card games like poker, bridge, solitaire and canasta, even housie, bingo, Lotto and many more, fall into this category. Table games involving sticks and balls evolved from efforts to bring outdoor games like pétanque, shuffleboard, croquet and lawn bowls inside to avoid inclement weather.

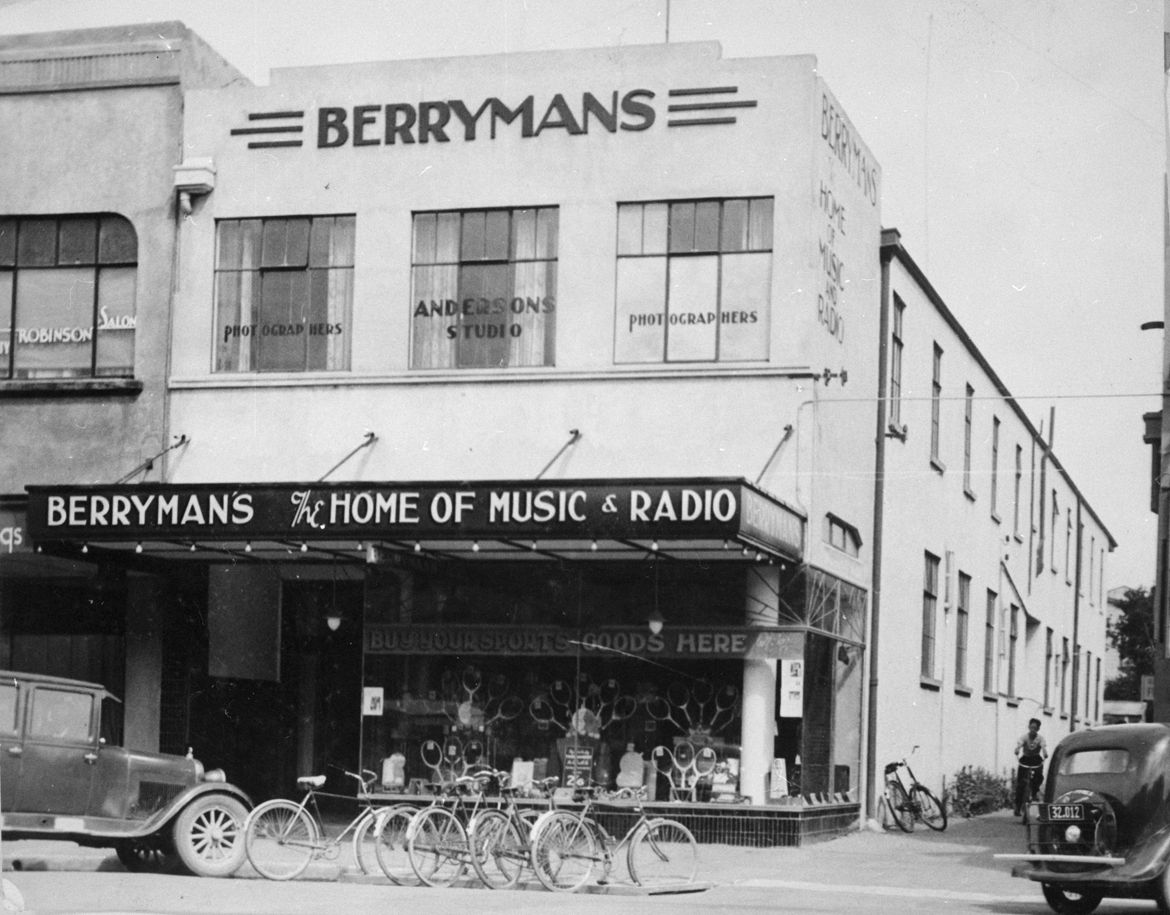

Shopfront of ‘Berryman’s, The Home of Music & Radio’, Broadway Avenue, where Palmerston North’s residents could see demonstrations of table-top ‘Taipo’ billiards in 1933. Photography: Snapshots Unlimited, c. 1937. Manawatū Heritage, 2009N_Bc223_Bui_2487

Mid-century DIY

The bagatelle board illustrated here is an attempt by a clever craftsperson to copy the games sold commercially. Their successful version was, as seen here, well-used and, apparently, well-loved. It is part of a large collection from the estate of Archibald Iverson Tiller, who died in 1993 at his home, 26 Ada Street, Palmerston North. He was the son of Ivy Rose Martin and her husband William Ernest Tiller. His father died when he was young and he lived in the family home with his mother for the larger part of his life.[v] It may have been Iverson who made the bagatelle board as he took carpentry and metal-working classes at Palmerston North Technical School during World War Two.

The placement of the nails is not as accurate as they might have been, although it appears that a pattern of circles was placed on the board using carbon paper which resulted in the smudges which are prevalent on the wood base. Copying a pattern on wood, metal or even cloth was often accomplished using carbon paper. The circular patterns for this game may have been sold at craft stores or model shops to permit craftspeople to duplicate the design of commercially produced units. The game board is in fair condition with evidence of use. The smudging around the holes is probably purposeful to delineate each target. Even today step-by-step instructions are readily available to show you how to make a bagatelle board.[vi]

TAIPO – Spirit of the Game

The word ‘TAIPO’ is pencilled near the centre of the game board. The name was copied from a bagatelle game that was produced and marketed commercially under the name ‘Taipo’. In te reo Māori the definition of taipō is ‘goblin’, but it is unclear if this was a word used by Māori believing it to be English or a word used by English believing it to be Māori.[vii] Why this word was selected for a commercially marketed product is unknown. Perhaps the difficulty of getting the balls into the holes or into a scoring position may have been the result of ‘restless spirits’. It may have been easier to blame the ‘goblin’ than the game player or the construction of a homemade game board. Another possibility is that it is named for the Tai Po district of Hong Kong.

Next time you play on a modern electronic pinball machine, consider how far the game has developed since its beginnings in 18th century France.

References

[i] Rodney P. Carlisle, ‘History of Pinball’, Encyclopedia of Play in Today’s Society, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, 2009.

[ii] ‘Bagatelle’, Wikipedia, URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bagatelle.

[iii] ‘Bagatelle’, Wikipedia, URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bagatelle.

[iv] New Zealand Advertiser and Bay of Islands Gazette, 29 October 1840, p. 2; Stephen Levine, ‘Jews – 19th-century immigration’, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, URL: https://teara.govt.nz/en/jews/page-1.

[v] ‘Obituary, Mr E.W. Tiller’, Manawatu Times, 30 April 1938, p. 13.

[vi] ‘How to make a bagatelle board’, URL: https://www.instructables.com/How-to-make-a-Bagatelle-board/.

[vii] Taipō, Te Aka Māori Dictionary, URL: https://maoridictionary.co.nz/; H.W. Williams, Dictionary of the Maori Language, 5th edition, GP Publications Ltd, reprinted 1992, p. 364.