The Puzzle

Cindy Lilburn, Collections Manager at Te Manawa, led me through the labyrinthine passageways to the collection store, issued me with gloves and unpacked the puzzle. It was here I began my investigation of this object, its origins, the 1924 British Empire Exhibition for which it was created, and the person who donated it to Te Manawa.

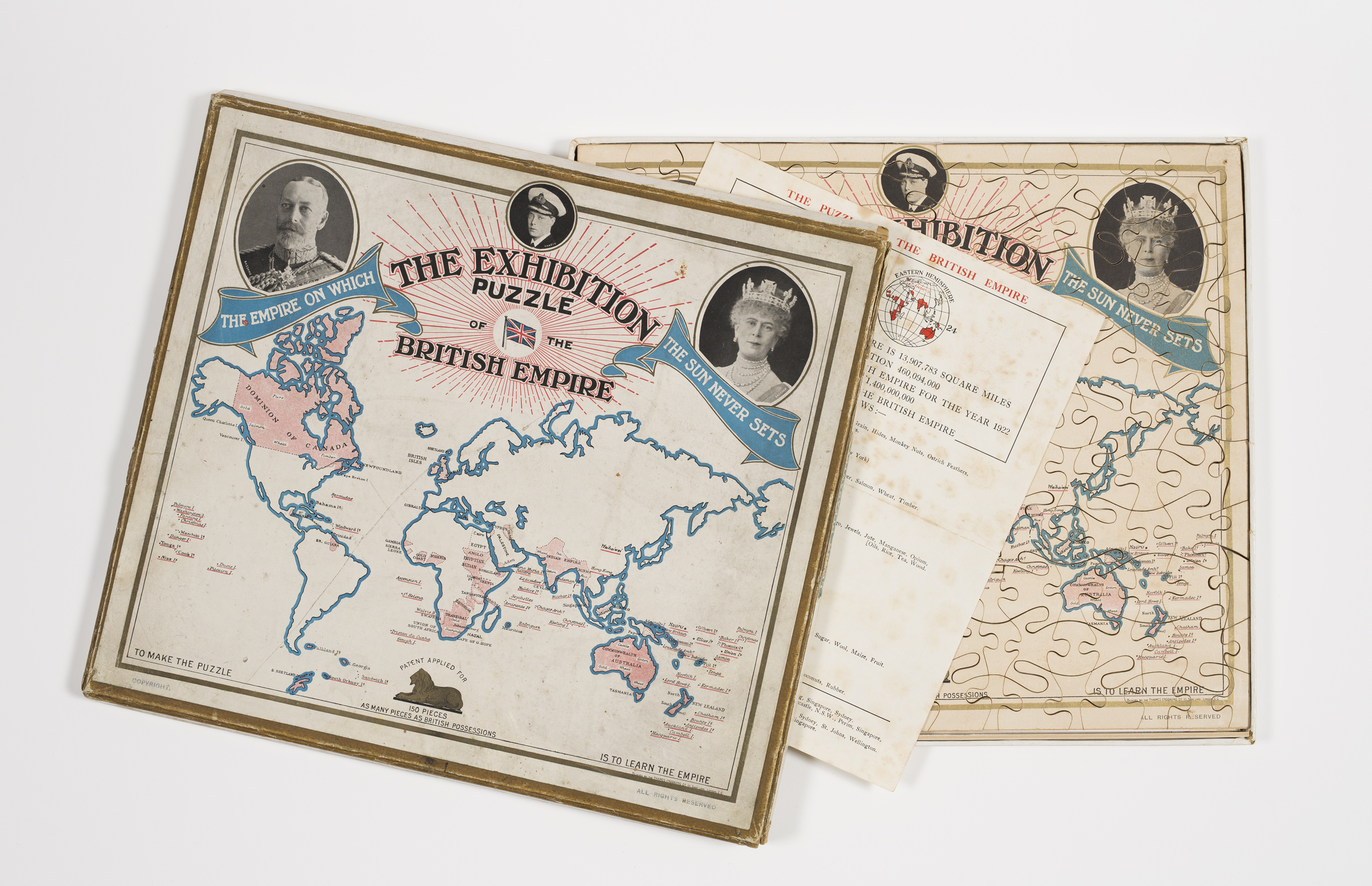

“The Exhibition Puzzle of the British Empire” has 150 thick pieces, packed in a cardboard box. Remarkably for something almost 100 years old, it has no pieces missing.[i] It might be one of very few copies left in the world.

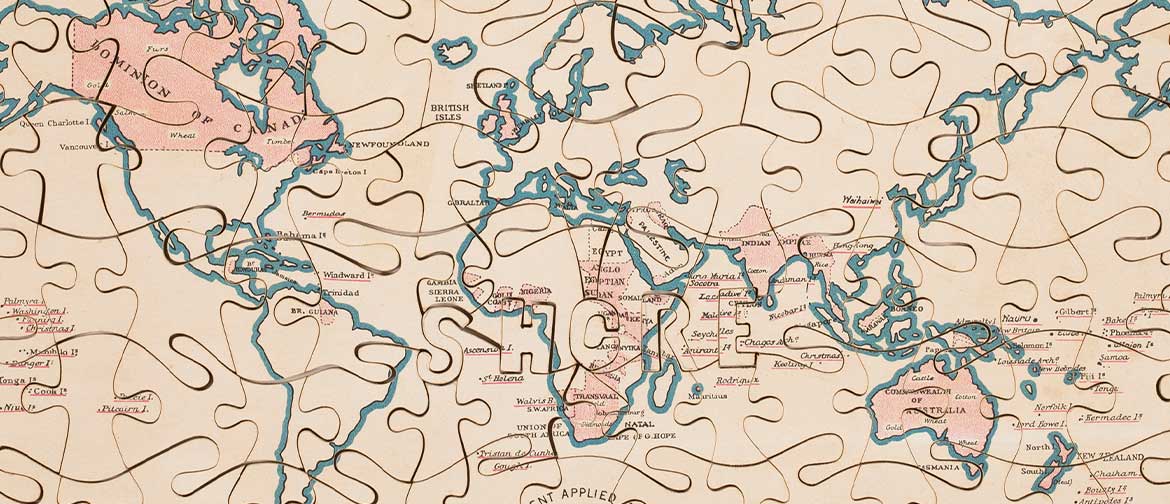

It’s not too hard a puzzle by today’s standards. The pieces are quite large and the shapes are distinctive. There is plenty of lettering to guide you on where to place the pieces – though you do need good close eyesight!

As you solve it you can refer to the lid of the box, which shows how the finished puzzle should look. Puzzle-makers at the time tended to avoid putting a picture on the lid. They didn’t want to make the solver’s task too easy.

It aims to teach the solver the location of all the territories making up the Empire – “To make the puzzle is to learn the Empire,” it says.

That could sound quite demanding, but it also says, “Learn Pleasantly”; the maker wanted the puzzle to be easy and fun to solve, so that you’d learn the locations of the different countries effortlessly. Although teachers in the schools of one hundred years ago could undeniably be strict, a feeling was developing that education ought to involve play, enjoyment, pleasure and kindness. My mother, aged eight at the time of the British Empire Exhibition and with a paralysed right leg, recalled the headmaster of Invercargill South School hoisting her up onto his shoulders and piggy-backing her around the playground!

The person who devised the puzzle is identified as “Dick Shore, inventor”. The British Empire Exhibition commissioned it from a firm called the Thames Engraving Company. Their office and workshop had its address at 111 Shoe Lane, London EC.[ii]

You could walk to Shoe Lane from St Paul’s Cathedral, the heart of the British Empire, in about fifteen minutes. A hundred years ago it was a rabbit warren of little printing, engraving and commercial art premises.

So far I have not succeeded in tracing either Mr Shore or the company. Maybe the company was short-lived and Mr Shore sought other pursuits. Whatever his identity, we can see, looking closely at the puzzle, what an ingenious fellow Dick Shore was.

There are 150 pieces because that was the number of recognised British possessions in 1924. There are nine extra pieces that fit with the others, spelling out Dick Shore’s name. This is highly unusual; usually there’s just an artist’s signature written or painted near the bottom.

A Short History of Maps as Jigsaw Puzzles

Dick Shore, besides calling himself the “inventor”, states that a patent has been applied for, yet patents are only granted for original inventions. To qualify for a patent, Dick Shore would have had to come up with something completely new in puzzle wizardry.

The concept of turning a map into a puzzle was a very old idea. It goes back to an 18th century English tradesman called John Spilsbury. His concept was to mount a paper map of the world on wood and then cut out the countries with a small saw. Each country was a separate piece, although probably the oceans were just one large piece, as it would be too difficult to cut out all the islands as separate pieces![iii]

Dick Shore’s application must have related to some other aspect of the puzzle.

We talk of “jigsaw” puzzles, from the type of saw that started to be used in the 1880s to cut the pieces. But it would have been a fiddly job, especially the small letters. There’d be every chance of leaving rough edges or tearing the paper.

Instead I think Dick Shore used a device like a cookie cutter, with very sharp edges. Or, more precisely, like 159 small cookie cutters assembled within a metal grid, each in the shape of one of the pieces of the puzzle. The grid would be placed over the thin plywood and clamped down tight. This would force the sharp edges right through the plywood, stamping out the pieces.[iv]

But this cookie-cutter device had been invented before Dick Shore came along.

More likely what Dick Shore wanted to patent was the concept of including small letters spelling his name. Unfortunately for him, a man named Theodore Bamberg was granted an American patent for small letter pieces in 1917, just seven years earlier than our friend Dick Shore. The patent number is US1256100A and you can find it online at Google Patents.

The Patent Office will have noted Mr Bamberg’s prior art and declined Dick Shore’s application. No particular disgrace – this happens to would-be inventors all the time! Even Thomas Edison had to fight to retain his patent (US223898) for the electric light bulb.[v]

‘The Exhibition Puzzle of the British Empire‘, 1924, gift of Leonora Elsie Coldstream, Te Manawa Museums Trust, 75/100/5

What’s In the Puzzle?

Let’s now get out our virtual magnifying glasses and take a close look at the puzzle.

The two larger photographs at either side show King George V and Queen Mary respectively. These cameo portraits were taken by society photographer Alexander Bassano. You can see his surname to one side of the cameos. He occupied a “grand studio” in Bond Street – an altogether smarter part of London than Shoe Lane!

Between the King and Queen, in a smaller cameo, you see a man wearing a cap. This is Prince Edward, who would become King Edward VIII upon George’s death in 1936.

The name “Vandyk” in Edward’s cameo denotes the photographer Carl Vandyk. From 1882 he owned a studio at Gloucester Road in London. Like Bassano, he took photos of the British royal family.

His company merged with Bassano’s in the 1930s to form what became “the” photographic studio for top people in British society.

The lettering at the top of the puzzle states proudly that the sun never sets on the British Empire. This was literally true, since the Empire had possessions all around the globe, but in a metaphorical sense the Empire did indeed have its sunset.

Historians argue about precisely when that sunset occurred: when India received its independence in 1947? When British possessions in Africa were decolonised in the 1960s? When Hong Kong was returned to China in 1997?

At the base of the puzzle is a lion, the symbol of Britain and the Empire, and also the logo for the British Empire Exhibition.

In the map, the possessions of the British Empire are picked out in red. Some are mere specks of islands, making it not difficult to arrive at the tally of 150.

The map is centred on Britain. From our point of view in Aotearoa, it’s nice that it has been designed so that we and Australia are grouped together. On many other world maps of the time our two countries are shown at the extreme right and left respectively – and on some maps New Zealand disappears altogether!

Dick Shore clearly felt that if children were really going to “learn the Empire” they needed to take in yet more information. So in addition to the puzzle, the box contains a paper insert filled with facts about the Empire. It’s filled with such edifying information as the area of the Empire, its population and the goods it exported.

Oddly, it lists coffee among New Zealand’s exports – a crop not grown here in 1924, let alone exported – while omitting wool, our second highest export earner. So although the puzzle wants you to learn about the Empire, it got a few things wrong relating to us!

[i] The Powerhouse Museum in Sydney holds another copy of this puzzle, though in inferior condition.

[ii] The story of Shoe Lane has nothing to do with shoes but takes us deep into medieval London.

[iii] Learn more about the history of jigsaw puzzles.

[iv] Bob Hodgson and Philip Poole are my informants here. What I’ve called a ‘grid’ could alternatively be called a ‘template’.