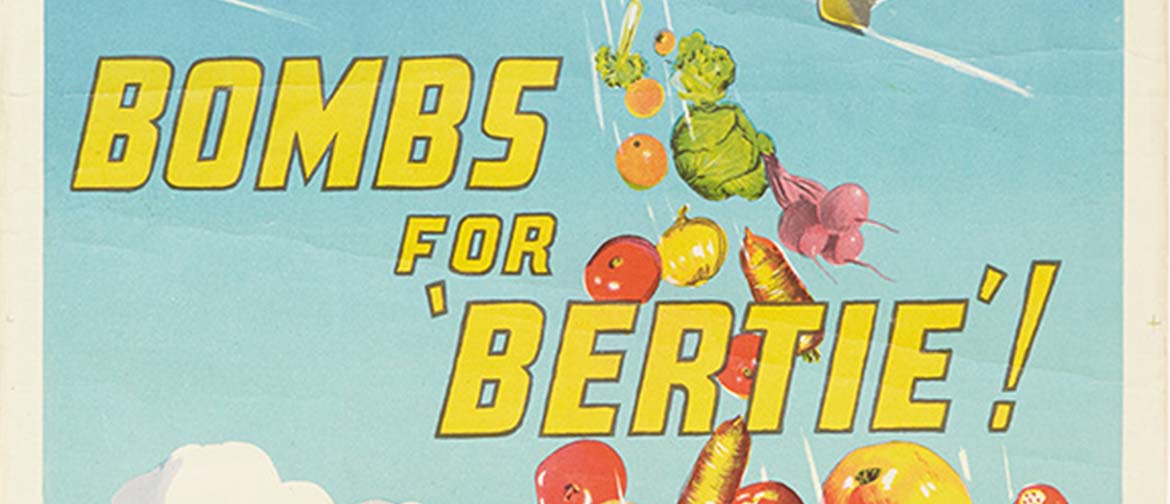

THE RISE OF BERTIE GERM

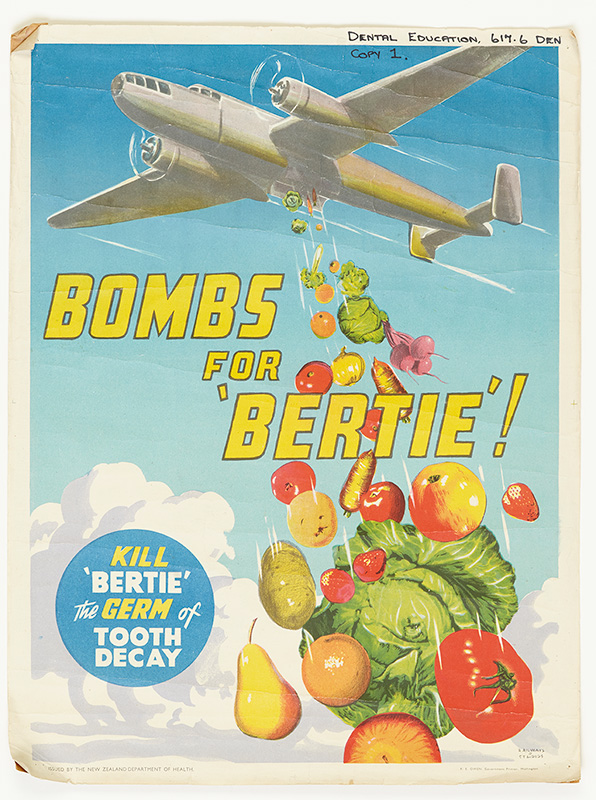

Bertie Germ gave some children nightmares. Active – supposedly – in the mouths of dental delinquents, he used his little pickaxe to excavate the holes that would subsequently lead to treatment at the ‘murder house’, or dental clinic. The ‘Bombs for Bertie’, which feature in one of the most famous dental health posters, showed how to combat Bertie’s ravages: good nutrition and the consumption of fruit and vegetables, rather than sugary treats, would help children avoid ‘the buzzer’ and retain their natural teeth.

THE SCHOOL DENTAL SERVICE

When the School Dental Service was founded in 1921, it reflected concerns about national efficiency. Recruitment of soldiers during the First World War had uncovered serious dental deficiencies among the younger generation, with even ‘fine strapping men’ finding it impossible to properly chew their food (especially army rations) (1). School medical inspections showed that 72 per cent of children had defective teeth, some seriously so. Reports referred to some school children who already had artificial teeth, and others whose untreated mouths were full of teeth so decayed and broken down that only stumps remained. (2)

School doctors blamed a range of physical disorders on poor teeth and ‘poisoned mouths’. Dr Elizabeth Gunn, a school doctor well-known in Palmerston North, wrote that “I do not wonder when I see some of the septic, foetid mouths of some of these children…that they are listless, inattentive and perverted!” (3)

(‘Perversion’ has not so far been linked with poor oral health, but thanks to contemporary research, conditions such as heart disease and diabetes have.)

The New Zealand Dental Association, Plunket and other agencies joined forces to urge state-funded dental treatment for children. The Health Department appointed former director of the Army Dental Corps, Thomas Hunter, as director of its Division of Dental Hygiene in 1920. Hunter elaborated the idea of a dental corps of young women, trained for two years, to work specifically on children’s teeth. By calling them ‘nurses’ he hoped to capitalise on the discipline and high reputation of hospital and Plunket nurses and to attract women from respectable backgrounds (4). Dental nursing was successfully promoted as a suitable job for women who would be better than men at handling young children, often a bothersome group for dentists to deal with. It was said to attract the ‘well-educated and well-heeled’. (5)

The work itself was more demanding than the ‘nice’ reputation of the profession suggested. Oral histories conducted with early dental nurses confirm an appalling state of child dental health. Despite an emphasis on preventive work and oral hygiene in the nurses’ training, they spent a depressingly large part of their time filling and extracting teeth. In 1925 the ratio of extractions to fillings was approximately 1.5 extractions of ‘unsavable’ teeth to every filling. A Dunedin-based nurse recalled: “I did 1700 extractions in a year. Sometimes the pus would run down your fingers. You have no idea what the mouths were like.” (6)

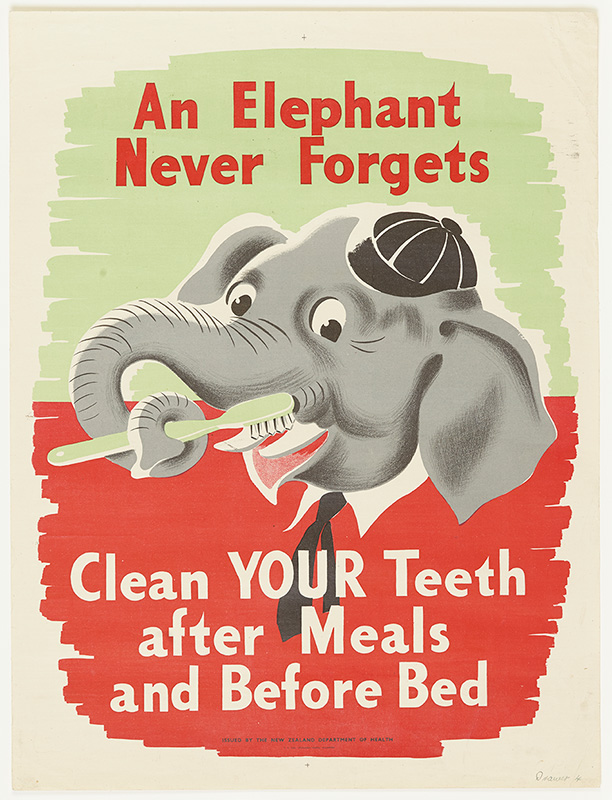

Regular teeth cleaning was a major part of education in dental hygiene.

Te Manawa, 89/103/32.

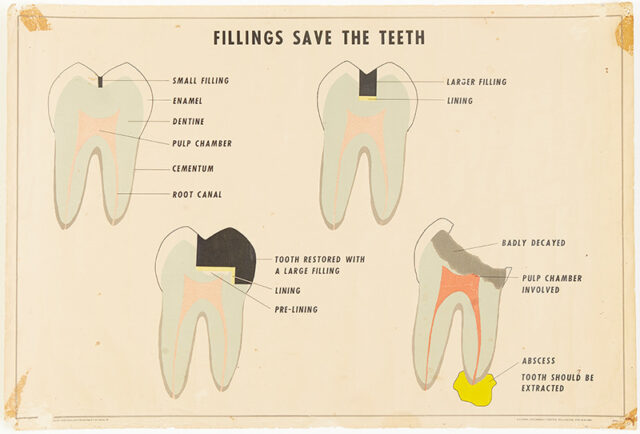

Images of teeth and their different elements were meant to give a sense of how decay could be treated and natural teeth retained.

Te Manawa, 89/103/34.

THE FIRST DENTAL CLINICS IN PALMERSTON NORTH

Among the first group of dental nursing graduates in 1923 were two who were sent to Palmerston North (7). There were no purpose-built clinics at this time, so when Central School offered up a room, the Department of Health accepted it. Nurses Baker and Mitchell started work soon after Easter 1923. The Department paid the nurses’ salaries and provided equipment, while a combined schools’ dental committee furnished the clinic and helped raise funds to assist the work. There was initially a five shilling charge on parents for each child treated, with ‘indigent’ children to be exempt. Not surprisingly, given the large number of teeth pulled, an early request from the Central School nurses was for a screen between the dental chairs “because the sight of an extraction rendered fractious an otherwise good patient and hindered the work.” (8)

Other clinics followed: College Street School first used the headmaster’s office; a dedicated building followed in 1936. In response to demand from country schools, a central dental clinic opened on King Street in 1933. Terrace End School gained its dental clinic in 1935. By the 1950s, specially constructed dental clinics were standard in most Palmerston North schools, including the first in the North Island to be erected at a convent school (in Pirie Street, 1944). (9)

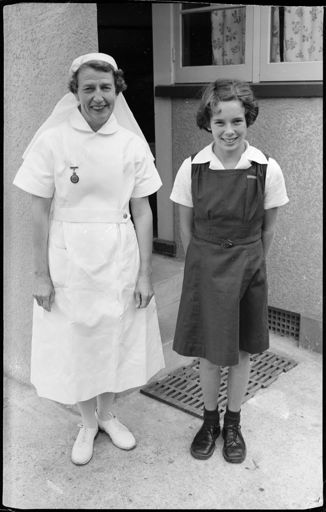

The dental nurses moved between clinics in Palmerston North and around the country. Some stayed for decades, however. Nurse Lorraine (Rae) Wimsett’s photograph appeared in the Manawatu Evening Standard in 1958 to celebrate her 30 years as a dental nurse. From a Palmerston North family, she was the first dental nurse at Feilding’s Manchester Street School in 1931, and came to Palmerston North in 1938 to work at the College St School clinic. At the time the 1958 photograph was taken (right), Nurse Wimsett was in charge of the Intermediate Normal clinic, and was treating the offspring of children that she had treated decades earlier.

MEMORIES

School commemorative volumes invariably mention the dental clinic or ‘murder house’. In West End the Best End, Val Mills writes of her encounters with Nurse Oates, who was at West End School the whole time Val attended. Nurse Oates’ “bright orange hair…clashed with the bright red uniform cardigan, creating a frightening effect for small children.

“I hated her white uniform most. The uniform had a starched front, and when Nurse Oates peered into my mouth her starchy bust pressed hard against my face…suffocation seemed the only possible result.” (10)

Val’s memories parallel those of many of us: unwilling consumers of the dental clinics of the 1950s. There was the child who went before you, returning with a note from the nurse which, alas, had your name on it, the reluctant walk to the clinic on the school grounds (Val once ran home instead, and was promptly returned to school), the waiting room in the clinic, and then the invasion of one’s wide open mouth by the nurse’s prodding hook-shaped instrument. Te Manawa holds many pieces of school dental equipment from clinics of the past, and we were all too familiar with their counterparts: the folding chair, foot-powered treadle drill, spittoons, rubber puffers, white cotton wool rolls that were shoved in our mouths, and the green plastic apron that was tied around our necks.

Given the high incidence of fillings in the pre-fluoride 1950s, few of us escaped the next step: the drill, agonisingly slow, since high speed drills were not in wide use in dental clinics before the 1970s (nor were local anaesthetics, except for extractions). Many of our mouths show evidence of the huge fillings, ‘prophylactic’ and otherwise, which were standard.

(Prophylactic fillings involved the drilling and smoothing of the natural fissures of the molars in an attempt to prevent future decay). (11)

But by the 1950s extractions were far fewer than earlier. School dental clinics on school grounds and the six-monthly appointments captured (sometimes quite literally) most primary school children by 1980.

Nurse Rae Wimsett outside the Intermediate Normal Dental Clinic in 1958. She poses with Judy Barlow, the daughter of one of Wimsett’s earlier patients.

Manawatu Evening Standard, Manawatu Heritage 2017N_2017-20_014684.

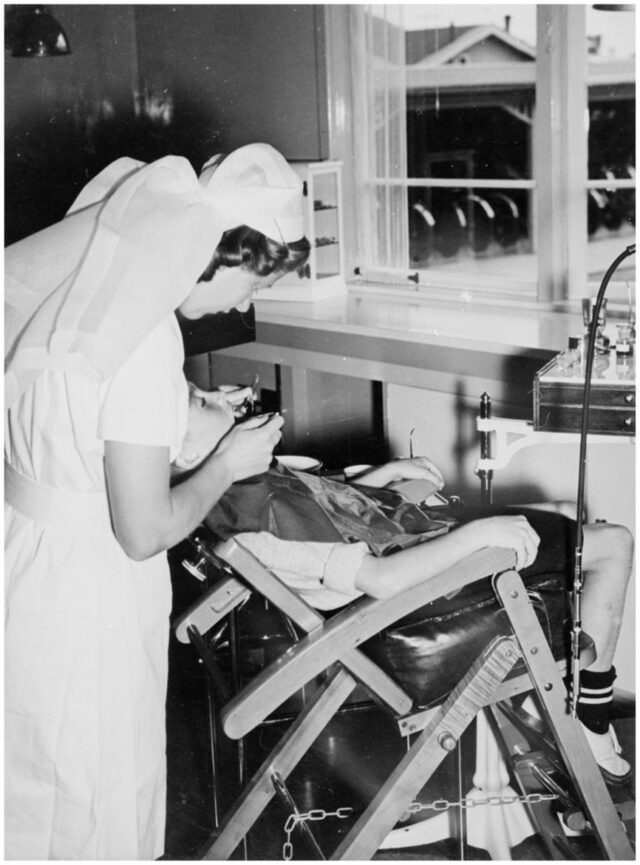

Savage Crescent resident Tony Evans posed in the Intermediate Normal Dental Clinic in 1947. The chair and equipment are similar to items held in Te Manawa. The image is part of a photo series commissioned by the Prime Minister’s Department to attract British migrants to New Zealand.

Manawatu Heritage 2010N_A175-67-1_004207.

EDUCATION IN ORAL HYGIENE

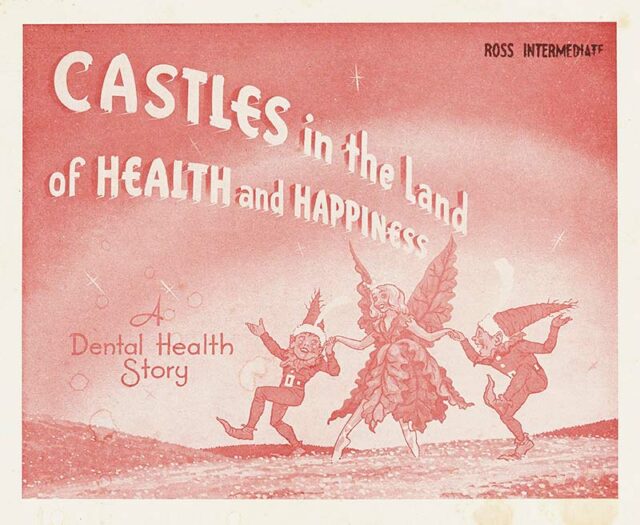

By the 1940s and 1950s the dental nurses had more time to devote to preventive education, and units of health education were formally incorporated into their work day. These included toothbrush drills with children, the use of glove puppets to tell dental stories, health education plays, and lectures to parents and groups. Te Manawa has a story booklet written by dental nurse Lorna Leslie and first published in 1954 by the Department of Health. Titled ‘Castles in the Land of Health and Happiness’, it tells the story of Molly and Peter, who go to a magic tooth castle and meet a soldier toothbrush and Princess Good Health. They are told to stay away from sweets and to eat their crusts, as well as plentiful fruit and vegetables. It bears the stamp of Ross Intermediate, and would have been in use there. Dental nurses were encouraged to undertake such creative work, and the Department of Health sometimes held competitions for stories on health-related topics.

Dental health posters represented this more benign side of the dental experience. Those in Te Manawa range from the colourful and attractive (‘Bombs for Bertie’, the elephant urging children to clean their teeth after every meal and before bed), to others with more technical information about tooth structure and the placement of fillings, presumably directed at adults.

‘Bombs for Bertie’ refers to the dreaded Bertie Germ, and is one of the best-known health posters from the post-war period. Probably issued in 1950, it is one of a series produced by the New Zealand Railways Advertising Studios for the Department of Health. Founded in 1920, the Railways Studios had a huge output of high quality creative work over multiple domains for more than 60 years. Other Health Department commissions included posters for campaigns against spitting, hydatids and rats, and promoting the use of handkerchiefs, healthy food and exercise. (12)

This Bertie Germ poster is stamped ‘West End School’ and could well have been viewed by Val Mills in the 1950s; I certainly saw one in the waiting room of the North Street School dental clinic later in that decade. Bertie Germ appears in other posters of the time. A related one which was especially popular with little boys (but not held by Te Manawa) shows racing cars driven by various vegetables and an apple cross the finishing line while Bertie Germ crashes out in the background.

The centralised School Dental Service did not survive the health reforms of the 1980s and 1990s, and nor did many of the clinics once child dental care devolved to area health boards. While fluoridation has meant that many more children not only retain all their teeth, but are caries-free, Bertie Germ is certainly not vanquished. Regional, ethnic and socio-economic differentials have increased in the twenty-first century and thousands of children annually experience ‘dental clearances’ – the extraction, usually under general anaesthetic, of all their teeth.

Margaret Tennant is a member of the Te Manawa Museum Committee who happens to have a mouthful of amalgam fillings dating back to the 1950s.

The Bombs for Bertie poster was an output of the Railways Department Advertising Studios.

Te Manawa, 94/157/11.

Health stories often countered their prosaic message with a fantasy element to appeal to children’s imaginations.

Te Manawa, 89/103/49.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alsop, Peter, Neill Atkinson, Katherine Milburn, & Richard Wolfe, Railways Studios: How a Government Design Studio Helped Build New Zealand, Te Papa Press, 2020.

Mills, Val, West End the Best End, Val Mills, 2012.

Moffat, Susan M., ‘From Innovative to Outdated: New Zealand’s School Dental Service 1921-1989’, PhD thesis, University of Otago, 2015.

O’Hare, Noel, ‘Tooth and Veil’: the Life and Times of the New Zealand School Dental Nurse, Massey University Press, 2020.

Rogers, Anna, With Them Through Hell: New Zealand Medical Services in the First World War, Massey University Press, 2018.

FOOTNOTES

1 – Anna Rogers, With Them Through Hell: New Zealand Medical Services in the First World War, Massey University Press, 2018, p.247.

2 – Susan M. Moffat, ‘From Innovative to Outdated: New Zealand’s School Dental Service 1921-1989’, PhD thesis, University of Otago, 2015, p.24.

3 – Margaret Tennant, ‘Missionaries of Health: The School Medical Service During the Inter-war Period’, in Linda Bryder (ed.), A Healthy Country: Essays on the Social History of Medicine in New Zealand, Bridget Williams Books, 1991, p.139.

4 – See Moffat, ch.2 on the establishment of the School Dental Service.

5 – Moffat, p.58.

6 – Moffat, p.89.

7 – Moffat, p.81

8 – Manawatu Standard (MS, 30 May 1923, p.4)

9 – Information from MS 6 March 1923, p.4, 30 May 1923, p.4, 9 November 1935, p.10, 20 December 1930, p.2; Manawatu Times, 25 January 1930, p.8

10 – Val Mills, West End the Best End, Val Mills, 2012, p.39

11 – Moffat, p.172

12 – Peter Alsop, Neill Atkinson, Katherine Milburn, & Richard Wolfe, Railways Studios: How a Government Design Studio Helped Build New Zealand, Te Papa Press, 2020, p. 29, p.91