POTATO POWER!

Spud guns operate on the same principle as water pistols. Squeezing the trigger creates air pressure, either expelling water from a reservoir or a fragment of raw potato lodged in the barrel. The spud gun warrior would keep a potato in his pocket and load his gun by pressing the narrow tip of the barrel into the tuber, twisting it sideways before pulling it out. This effectively blocked the barrel so that when the trigger was squeezed sharply, compressed air would fire the pellet with enough force to sting bare skin at short range.

IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE SPUD

The first spud guns were marketed by American entrepreneur Joe Cossman in the 1930s. He bought the tooling for $500 from the inventor, who clearly had none of Cossman’s marketing nous. Cossman knew that the US was experiencing a potato glut and persuaded the Dept. of Agriculture to back his advertising campaign. He sold two million guns in six weeks. This left him with 70,000 unsold guns. Discovering that they worked as well with papaya, he offloaded the remaining guns on the Mexican market.

Clearly no patent existed for spud guns because there were many different types available during my own childhood in the 1960s. Like Te Manawa’s example, they were usually made of ‘muck metal,’ the popular term for any cheap alloy containing aluminium, lead, zinc and varying amounts of other metals. The virtue of such alloys was their low melting point, and they were widely used in the diecasting of cheap, mass produced items, particularly in the toy industry. Their disadvantage lay in being relatively fragile compared with a pure metal such as steel or aluminium.

MADE IN NEW ZEALAND

Te Manawa’s ‘Liquitater’ is an interesting item because it was made in New Zealand. Before the scrapping of import licences in the 1980s, many small New Zealand businesses made toys. Not only did customs duties add to the price of imported toys but the toys themselves sold quickly on their arrival and were unavailable for most of the year. This created a ready market for local products, most of which were made in small, even home-based workshops. They included live steam models, accessories for model railways and the iconic Fun Ho! range of vehicles manufactured in Inglewood.

Producing a spud gun from castings would not have required hi-tech equipment. By using low melting-point alloys, the parts could have been produced quickly and cheaply. Import restrictions made such small scale local enterprise viable.

‘Liquitater’ spud gun, c. 1930s – 1970

Made in New Zealand, maker unknown.

Diecast aluminium model pistol with silver paint coating.

Collection, Te Manawa Museums Trust, accession no. 2007/74/42.

BOYS AND GUNS

Public opinion has turned against toy guns in recent decades. The chief driver has been mass shootings such as the terrorist attack at Christchurch’s Al Noor mosque and widely publicised killings in U.S. schools. Allied to this is a revulsion at any form of fantasy violence and the belief that toy weapons reinforce gender stereotypes.

After the shootings at Sandy Hook elementary school in Newton, Connecticut, public opinion was such that a first grader in Montgomery County School was suspended for a day after pointing his finger at a classmate and saying “pow” (1). Closer to home, Marlborough Boys’ College was temporarily locked down after it was believed a student was carrying a gun. It proved to be a toy revolver (2). When Prince George was photographed playing with a toy pistol while the royals were watching a polo match, there was a media storm in which his mother Kate (aka Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge) was accused of “getting it wrong” (3).

Many educationalists take a more nuanced view, claiming that all imaginative play is an essential part of cognitive development and that children learn the boundary between fantasy and reality as part of the process. New Zealand educationalist Pennie Brownlee sums up this argument:

“Imaginary weapons…fulfil the needs children express as they play. Children have been doing this since the beginning of human existence…the resulting weapon is never going to be perceived as ‘real’” (4).

Brownlee and others draw a line between toy replicas of real guns – the AK-47 is particularly popular – and water blasters and Nerf guns which are brightly coloured fantasy weapons. Research suggests that there is no proven connection between playing with toy guns in childhood and committing gun crimes as an adult (5). Cruelty towards animals is a more reliable indicator of sociopathic tendencies (6).

SPUD GUNS IN THE 21ST CENTURY

Spud guns were not a high profile toy in their heyday. They were a stocking filler, or a novelty bought with a couple of weeks’ pocket money. Today they are sold as retro curiosities such as a father or uncle might buy for a child, having half an eye on his own childhood.

Like all toy guns they are still marketed as ‘boys’ toys’ and my own memories of playing with a spud gun are of mock battles with neighbouring boys. The waste land running from behind St James School to lower Te Awe Awe Street (which is now Chilton Grove) provided a suitable No Man’s Land of coarse grass and lupin bushes.

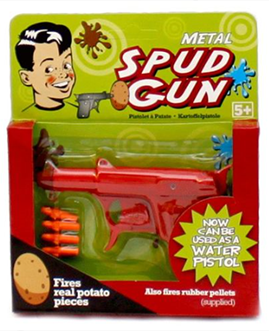

Available from the UK’s ‘Wicked Uncle’ online store, this spud gun is a close copy of the original, being made from cast metal. The packaging is deliberately retro in style and emphasises that the gun is a ‘boys’ toy.’

This plastic spud gun is marketed by the Real Groovy online store and has even more evocative retro packaging. It is both a “Blast from the Past” and of “Premium Vintage Quality.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Veart, David. Hello Boys and Girls; A New Zealand Toy Story. AUP, 2014

Kessler, Debra. Nerf Guns: What are we afraid of?

Parent Co. Toy gun debate can be incredibly confusing for the parents of boys.

ParentMap. Weapons Ban: Just how bad are toy guns for kids?

Brownlee, Pennie. Bang Bang! You’re Dead. NZ Journal of Infant and Toddler Education, Vol 10 no. 2, 2008

FOOTNOTES

1 Washington Post, Jan 2, 2013

2 Stuff.co.nz, July 5, 2018

3 NZ Herald, 12 June, 2018

4 NZ Journal of Infant and Toddler Education, Vol 10, no.2

5 Today’s Parent, June 22, 2012

6 Parent Co, May 2, 2017